Remembering to Forget: The Curious History of the London Stone

/One of the lesser-known mysteries of London, England, is tucked away between the Tower of London and St. Paul’s Cathedral. At 111 Canon Street, inside a WHSmith (a British book retailer and, incidentally, the inventor of the ISBN catalogue system) behind a protective grille sits the London Stone. No one knows the purpose or significance of the Stone other than the one imposed upon it by generations of Londoners and writers. Many have mentioned it over the last 900 years as a significant object for London’s history, but no clue remains as to its origins. In a sense, it is historically important because people have made it so.

Wikiepdia, London Stone, photo taken by Lonpicman, 13 January 2004.

So what do we know about the London Stone?

In 2010, John Clark wrote in Folklore a concise and telling history of the London Stone. His article, “London Stone: Stone of Brutus or Fetish Stone—Making the Myth,” rejects a “traditional saying” that supposedly reveals the London Stone’s purpose: “So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe / So long will London flourish.” Clark explains that Brutus, the apocryphal founder of Britain and descendant of the Trojans, supposedly founded London and laid the stone as a talisman to ensure its future prosperity. While this is clearly a fabrication, Clark questions even the claim that it is a “traditional” saying – in fact, it first appeared in an 1862 publication. Many other myths about the London Stone are traced back to writers, and none reveal the Stone’s true background.

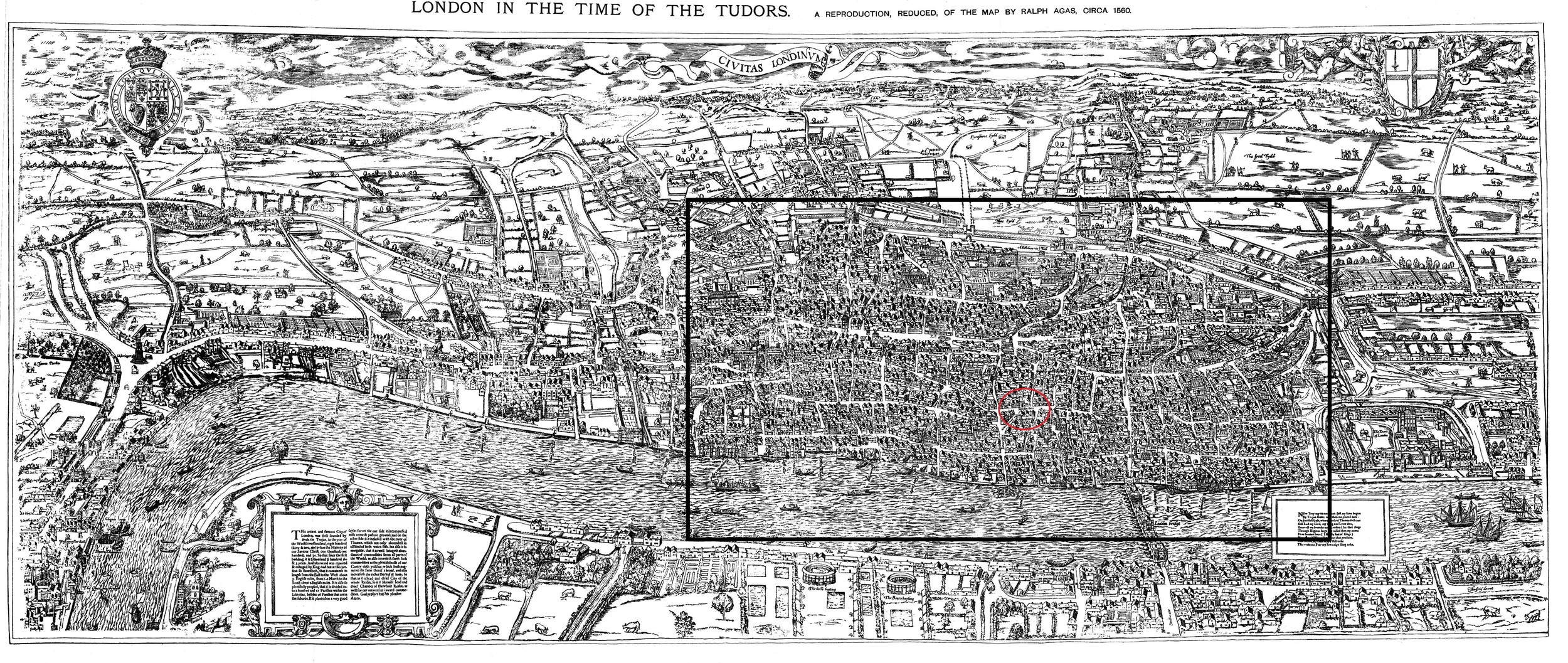

The earliest reference to the London Stone dates back to a list of Canterbury Cathedral properties, written between 1098 and 1108. It lists a property given to the cathedral as “at London stone.” At the end of the 12th century, the first mayor of London, Henry Fitz Ailwin, was said to have lived at the London Stone. It’s also claimed that in 1450 the rebel Jack Cade struck his sword against the London Stone to claim his right to rule the city. However, none of these accounts explain the stone’s significance in relation to these people and events, or even if it was significant at all. Perhaps it was just a convenient landmark. It appears on a 1550 map of London as well, but again without any explanation of its importance:

Conjecture about the London Stone is not new. In 1598, John Stow theorized about the stone’s origins as the centre of the city, or simply a marker for a family named Londonstone, but ultimately concluded that “the cause why this stone was set there, the time when, or other memory hereof, is none.” Stow’s contemporary, William Camden, wrote in 1607 that the stone was a marker from which the Romans had measured distances to and from the city throughout Britain. By 1720, John Strype believed that the stone was druidic in origin, an artifact of ancient Britons that had survived the Romans and Christianity to become an object of historic significance. By the end of the 18th century, some believed that the stone was in fact a current or former palladium, referencing the statue of Pallas Athene stolen from Troy by the Greeks and foretelling that city’s doom.

The notion that the stone was London’s talisman, or at least had some historic or mystical connection to the city, was propagated throughout the 19th century. An 1862 note to the publication Notes and Queries, remarked that “Tradition also declares it was brought from Troy by Brutus, and laid down by his own hand as the altar-stone of the Diana Temple, the foundation stone of London and its palladium.” Signed “Mor Merrion,” the author seemed a mysterious figure until John Clark’s contemporary research revealed that it was a mistranslated pseudonym for Richard Williams Morgan, a Welsh patriot, writer, and strangely, an ordained Bishop of the Ancient British Church. Morgan was one of the first to explicitly link the stone to Brutus and London’s founding – claiming already in 1862 that this “traditional” saying confirmed its mythologization, though this was the first appearance of it!

As Clark outlines, Morgan weaved together Welsh and British myths and combined the London Stone, Brutus of Troy, and the Welsh figure Prydein ab Aedd Mawr to explain Britain’s founding and historic roots across the United Kingdom and to ancient cities of Rome and Greece. Later Victorian writers called the stone a “Fetish Stone” or a “foundation-god.” They agreed that the stone was an integral part of municipal customs, but not with Morgan’s historic claims stretching back to Troy.

In the 20th century, writers began to ascribe it a more mystical character. It was supposedly located on “ley lines” through the city of London as a crucial part of its “sacred geometry.” Its presence and legend has been incorporated into new age mysticism, again fulfilling a role as London’s talisman. Today, after being moved several times over the centuries (perhaps removing it from its ley lines?), it now sits behind a magazine rack in the WHSmith store. Though we have never visited it, it undoubtedly escapes notice and remains a guarded palladium for London. Which – to date – has yet to fallen to a foreign conqueror. Except William the Conqueror, but surely they were like family after a few kingly generations.

The London Stone is a strange piece of the city’s history. Its supposed use has shifted over the years, as different generations of writers reacted to the ancient artifact that lay in their city throughout, as far as they knew, its entire history. Literary movements and personal bias all influenced the various interpretations of the London Stone, some more reasonably than others did. Yet no one can definitively describe its origins or its actual importance. The ambiguity surrounding the Stone has allowed it to occupy this fluid space between fact and fiction.

We generally like to claim that “history” is fact, while its relation, “myth,” is fiction, but the two may be siblings instead of distant cousins. The history of the London Stone has been passed from generation to generation, never quite the same as what had been said before, and even today, we used the work of a folklorist to trace its story rather a historian. Throughout it all, the historicity of the London Stone is unquestioned – surely it is important, it’s the London Stone! This circular logic, while obvious when pointed out, reveals an unfortunate truth of history itself. History becomes history because we say it is so, rather than any absolute claim to its importance or relevance.

If no one could ever say for certain why the London Stone was so important, then why did we remember it? If the London Stone can become part of the history of London by virtue of its repeated mention, then what else do we remember as history for the same reason? What does this say about how historians will remember Kim Kardashian?

Joking aside, let’s take it a step further – how is this “history” currently popularly remembered? Unless you live in London, England, and can go visit the WHSmith right now, you likely encountered the London Stone’s history primarily here on our blog. Though most internet users are more likely to have visited its Wikipedia page than Clio’s Current. There we can see the history of the London Stone (largely drawn from John Clark’s Folklore article) enshrined as part of London’s history. Wikipedia calls it a “historic landmark,” but also lists it as a “mythological object.” Thus, Wikipedia digitally preserves the history and myth of the London Stone on its servers for our foreseeable future.

Wikipedia. Image extracted from page 559 of volume 1 of Old and New London, Illustrated, by Walter Thornbury. Original held and digitised by the British Library.

The London Stone and its digital memory leads us to other questions. Imposing meaning and structure on the past, be it through history- or myth-making, is how we make use of it. We have to be able to pick out the important things to remember and the less important things to forget – and this understandably changes based on your identity, the questions you ask of the past, or any number of factors. But what happens when we have collectively remembered something which is arguably not important at all, like a hunk of stone? But now, instead of old books gathering dust in the last row of the library stacks, that memory is preserved on computer servers for essentially the rest of human history and immediately accessible. This question applies to the Wikipedia page on the London Stone as it does to the billions of files stored on computers and servers around the globe. The digital world will be remembered by computers for far longer than any human ever could.

How do we forget something that is no longer worth remembering?

We can’t! Until we encounter an apocalyptic scenario, history in the digital age is now limitless. As we digitally remember more and more about the past (including the myriad of different meanings for it), history effectively becomes a larger and larger data set of human memory and experience. It is historians who set up the guideposts for you, the reader (or user), to explore this immense body of data. In the vast wilds of the past, historians give you a map – or maybe a guided tour. By telling you where to go, they are also telling you where not to go.

In 2015, we have to remember to forget sometimes.